Pricing Effectively

My notes from a McKinsey textbook on pricing (and why pricing is important now, more than ever)

Intro

Hi! Welcome to all the new subscribers coming in from my Zigen writeup. If you haven’t read it yet, go and check it out here and remember to click the link to the full PDF writeup (there is a link at the top and bottom of that substack piece) if you’re interested in the idea as heaps of work went into the long-form version. Thanks to everyone who has provided feedback already. I’m learning heaps!

Pricing power

I have just finished reading a rather dry book from McKinsey & Co called ‘The Price Advantage’, which was published in 2003 and written by Marn, Roegner, Zawada. You’re probably wondering; why voluntarily subject yourself to such an experience? The answer is… the best motivator of all in our monkey brain: ‘fear’. Fear of inflation rising to levels not seen since years before I was born. More precisely: a fear that I don’t really know what ‘pricing power’ is, despite Buffett raving so much about it. So I grabbed this book (it came recommended) and gave it a read during my COVID recovery. A role model of mine on Twitter asked me to share any interesting clips or thoughts, so here they are. I hope you enjoy this slightly different piece on my learnings from ‘the Price Advantage’.

First few lessons

Why my fear is justified is my first learning from the book. (1) Buoyant economic conditions create complacency in pricing - what many managers (and investors) may attribute to pricing power, can actually be attributed to market trends, economic conditions, money printer going brrrr, technology developed outside of the firm, and other factors beyond the firm’s control. Pricing is less of a concern during the good times, but becomes absolutely critical in the bad times. We’ve had a decade of strong growth and dropping inflation - now inflation is on the rise, the yield curve listened to Munger too much and has inverted, people are calling for a recession and input costs are mooning. Buffett has a skinny dipping quote on this conundrum which I’m sure you’re familiar with. When the tide goes out, I want to be wearing a wetsuit, with goggles, flippers and holding a speargun (if possible).

In 2003, the authors were cashing fat cheques by providing consulting to firms who had no clear pricing strategies. For some reason, many firms were not thinking about arguably the most important thing they were doing - pricing their products. Enter the second main learning from the book. (2) Price is the most sensitive profit lever available to managers, as small changes can have massive consequences to profits. They remarked:

No single lever available to management can boost profitability more quickly than even a slight improvement in average price levels.

To demonstrate, in 2003, on a Global 1200 dataset (quite dated), a -5% drop in price required an increase in volume of 17.5% to break even. Reducing price to boost volume is rarely a good idea. However, increasing prices by 1% on the same dataset increased profits by ~11%. How? On average, the percentage of variable costs to vs fixed costs leans heavily towards ‘variable’ (among that dataset). As volume increases, so too do the variable costs, reducing the potency of the higher sales number. On the other hand, a price increase adds no extra variable costs, and yeets the added revenue straight to the gross profit line item. So the postive/negative effect depends largely on on the fixed cost/variable cost cocktail in the company.

Anyway, the learning here is that ‘messing’ with pricing could be very positive, or very negative, to the bottom line. Especially for large variable cost businsses.

Another factor which is worth bearing in mind is that pricing relates to pride in a brand and customer perception. In order to increase prices, a firm is making a ‘take it or leave it’ statement that their product is truly worth more than it once was. By doing this, they are betting that their customers will agree and pay up more! Its hard to be held accountable in this way as a manager given the consequences of failure in this field can have a dire impact on the bottom line, and worse yet, have long lasting impacts on consumers who might paint the firm as customer-gouging or ‘tricky’. A bad reputation on price is hard to shake.

Because of the above factors (sensitivity of the lever, dire consequences of failure), many managers were afraid of messing with prices, and did not have a regimented pricing strategy. Wouldn’t it make sense to leave ‘the market’ to work things out and liaise regularly with the sales team on how things are going? And from an investor’s standpoint - approaching the pricing conundrum with investor relations is hard - that information is often seen as the firm’s secret recipe of 11 herbs and spices. Getting them to spill their guts isn’t easy, so why bother asking?

Well, my view (newly formed) is that pricing strategy matters all the time, but now more than ever. All costs are rising with inflation. Especially those variable costs mentioned earlier. The ability for a firm to pass on those increased costs just to remain at prior profit levels is critical. If costs increase by 5%, and the costs can’t be passed on, a 17.5% volume increase (during what might be a recession) seems ambitious. A price increase (whether to maximise profit, or cover increased costs) and the way firms can execute that price increase, are explained in the book. Failing in this space means the business will have their gross margin compress and if there isnt enough fat there, they will incur losses.

Three levels of price managment

Now for my third learning: (3) there are three ways to cut up price management - some are related, all are important.

These are:

Industry monitoring.

Product market analysis.

Transactional rigour.

On Industry monitoring - firms may fail to recognise supply deficits in their industry and not raise prices. Errors in this field are typically ‘opportunity costs’. An economist’s explanation might be that demand is outstripping supply. How to enhance pricing power: monitor economic movements very closely and act quickly when opportunity presents itself, as the cure for structurally higher prices is high prices - your competitors (present or future) will surely notice and move in to compete with you lowering them again. The window of opportunity is small, but still there.

On Product market analysis - firms may fail to recognise the brand power in their services, and charge lower prices than they otherwise could. A marketing person might describe this as an internal brand issue. How to enhance pricing power: the crux of the firm’s focus should be the generic pricing lists (internally, or externally shown - or both). It is critical to understand how the customer perceives your price list before making a price increase based on the product market strategy (i.e. how is the benefit of your service perceived, and how is the price/value factor perceived). You must also know what the customer perception of your competitors is, to the extent you can obtain that information. This delicate balancing act is explored more in the ~VEL~ further down.

On Transactional rigour - firms may fail to adjust and optimise pricing (including incentives and discounts) for individual customers. Typically a business development person will identify this issue. How to enhance: know your ideal customer and aggressively seek them out. Discard bad customers or increase prices for them, rather than increasing variable costs to simply grow regardless of the target customer. By focussing on higher margin customers at a lower growth rate, instead of lower margin customers at a higher growth rate - the firm will generate more profit. This requires strong analytics and data, as well as strict discounting/write-off policies.

Benefits to the customer

In comes the fourth takeaway. (4) There are three kinds of ‘customer benefits’ a firm should think about, and a business should see where it excels and where it can improve in order to maximise pricing power. These are critical, particularly if you’re trying to improve the execution of pricing power via the second level of price management (product market analysis). These benefits also need to be balanced against the firm’s competitors and their benefits:

Functional benefits (quality and breadth of product/service features)

Process benefits (ease of using the good/service, easy re-ordering and payment, good tech support and customer facing services)

Relationship benefits (enjoyment of brand power, prestige)

Firms (and investors) should have a decent grasp on where the company sits across the competitive landscape in relation to these factors. If strength is perceived across all three, make sure price strategy (2) is being pursued properly and pricing power is being exercised.

One-stop-shops

Data cited by the authors showed that solutions providers (one stop shops) generally were able to command higher prices over providers of goods or services that was mainly integration (putting together or arranging components for a specific client), specialising in the creation of components (one part of the process), or bundling components together for generic circumstances. The theory here is that a customer is prepared to pay more for the convenience of having it sorted (with a full-stop).

While not mentioned in the book, a thought here: would vertically integrated businesses be less likely to suffer as a result of price volatility across the value chain, given suppliers and different players in that process won’t demand a cut at various touchpoints? If so, this supports the ‘one-stop-shop’ thesis in a way as well.

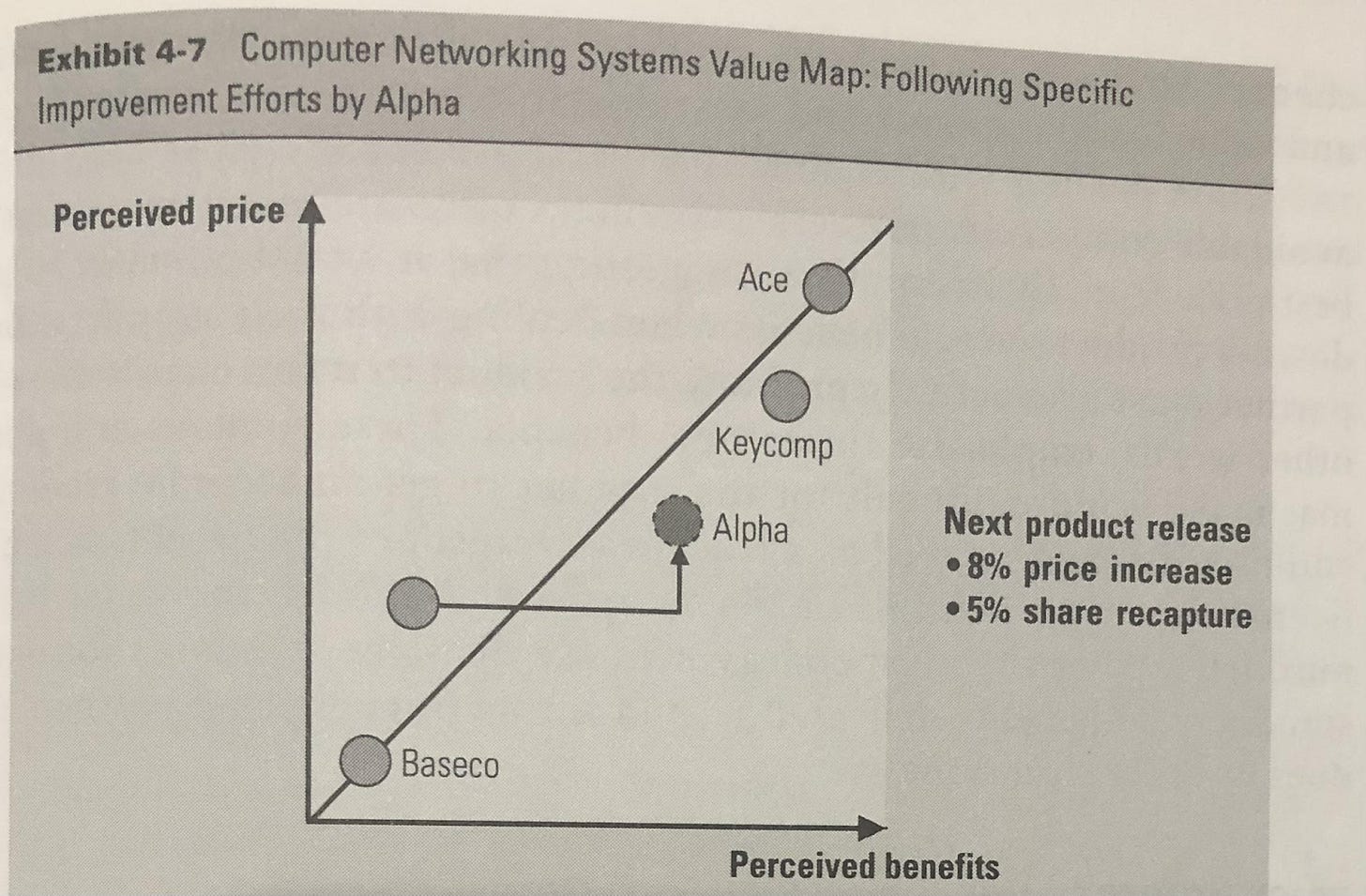

The VEL

Learning five. (5) McKinsey consultants make things overly complex but sometimes its cool to think about what they say. The Value Equivalence Line (VEL) is a chart which shows that (theoretically) within a product market there is an equilibrium between perceived prices (Y) and perceived benefits (X) of a product or service. In a perfect world, a variety of offerings will sit along the VEL, where consumers pay exactly what they think is a fair price for a product of a certain calibre. Not all offerings along the VEL will have the same levels of demand (or TAM) in size. The chart looks like this:

Yep, thats a photo from my phone. Thats the kind of tight ship we run here. All quality.

If you’re below the VEL (Company B) you’re in a ‘value-advantaged’ area and going to absolutely decimate your rival along the VEL (Company A) since you’ve got the same perceived benefits, but a lower perceived price. You should really be moving up towards A, and that may take time for your product’s reputation to demand a higher price. Alternatively, you can remain below “A” if you want to capture their market share. At a point though, you need to re-price to grow profits instead of market share. Company “A” might even drop prices to come down and meet you halfway if they go on the defence, which means you’ll get less TAM and should think about price increases sooner. Company D is value disadvantaged and can be expected to lose market share from E - people think the company is overpriced for what it offers. Company E is more appropriately priced for those features of Company D, and they will gain market share. Hope that makes sense! Stay with me…

When do you want to move around the VEL?

You want to increase your price and your perceived benefits at the same time. This might be scary, because by increasing your price, you might no longer appeal to the same market as “Baseco” here, where you once competed for the dregs and degenerates in your product market. But, you move into a market with Keycomp and Ace - this might be a larger TAM with potentially higher margins. If so, your product is nearly as good as theirs, but cheaper! You’ll start to take market share from them. You should only do this if the TAM is worth capturing. Once the TAM is gobbled up, think about increasing your prices. Note if stronger benefit was perceived in rolling up and dominating the dregs of this market, you could pivot right and down to try and eliminate Baseco and mop up the rest. Its dynamic, and a theory.

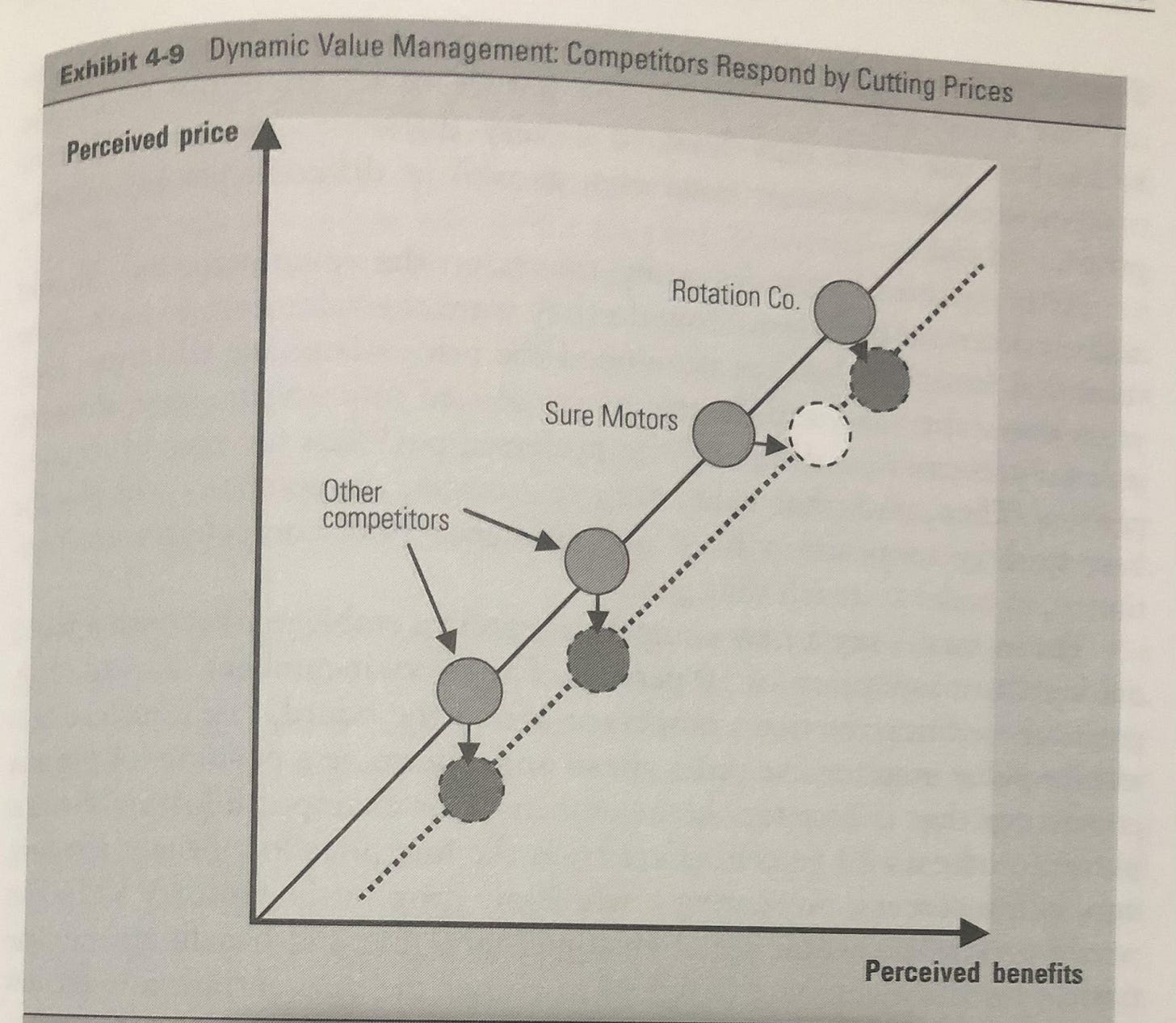

Looks sound. But wait.. this isn’t a foolproof plan:

If you improve your features but not your price (as ‘Sure Motors’ do here) - with the hopes that this will cause you to take TAM off a market leader (i.e. Rotation Co), and your competitor just drops their price to match yours, you might accidentally shift the VEL completely in the customer’s favour without gaining a meaningful market share. There is no longer a value advantage between you and Rotation. Spare a tear for the players in the market who can’t match the product improvement you put forward. They will lose out, being perceived as ‘worth less’ when both your product (and your main competitor’s) products have either improved, or dropped in price. This make it critical to notice when fierce price competition is emerging and avoid owning companies that don’t have the capacity to improve their products (lack of talent, capital - or both) operating usually at the bottom of the quality spectrum.

Ok - VEL. Why is this useful? To be honest, I just liked the intellectual aspect of thinking about competition this way. But firms should definitely have their own map somewhere, even if it doesn’t look as precise as the VEL. Whether they share it or not is another thing - its useful and confidential info. But it might be worth asking management about where they think they sit relative to the price and quality perception of their peers, as this might give you some clues as to pricing power under the second price management strategy. Investors can then DIY a map in a rough state to know where the company sits if competition heats up.

M&A

Learning six. (6) M&A presents a unique opportunity to raise prices. Customers may anticipate pricing changes when there is a new sheriff in town, especially if there is some kind of PMI, and especially in B2B structures. If the company can articulate how the M&A has brought value to customers (functional, process or relationship benefits along the value axis, as described in more detail earlier), then M&A presents a unique opportunity to “reset” discounts, markdowns and deal policies (striking at the heart of the the third price management strategy above). In this way, a company can exercise its pricing power and an opportune time.

M&A will also attract the attention of competitors who will watch for the new combined business’ moves - allowing you to potentially hit a reset on industry price floors or pricing strategies, if you raise and your competitors raise also - the customers might lose out but both businesses do well. A risk or two here though (beyond the competition / anti-trust stuff): merging with a company that sells a lower standard product vs the primary product of the acquirer means the acquirer should ensure that any increase in the quality of the lower standard product is linked with an increase in price for that product (as a result of their value add). Seems scary, since you don’t want to alienate these new customers who are used to lower prices. But if you leave it too late, you’re delaying ripping the churn bandaid off and this isn’t a good use of pricing power. Another risk: merging with a company and forcing upon it the acquirer’s pricing model is often a bad idea. It may be that optimising the acquired company’s pricing structure is the better call. Management should be dynamic in the way they approach post merger pricing.

M&A also opens the door for another opportunity on price: resetting KPIs for staff to instead focus on higher deal sizes and fatter margins, instead of volume. This leads to learning seven.

Use the right KPIs

(7) Staff, but especially the sales team and the c-suite, should be rewarded on scoring higher margin deals, not a larger number of deals. Picture ‘top salesperson of the year’. You’re imagining a big number above their head, reflecting total deals done. Sam has been busy on the phone, chatting away. He writes lots of deals. More is good! How does Sam write so many deals? Well, his clients love him. They love him because they screw him. Sam is a pushover, and offers discounts to lure clients over the line all the time. He’s busy because he calls all the low margin customers that nobody else wants. This is wrong. Sam should be punished, fired, PUT IN THE BIN. Why? Remember our price vs volume discussion at the start. The best salesperson only pulls out the discount card when absolutely necessary - they pursue the clients that are prepared to pay up for quality - and he sells them quality, charging full price. He has left the penny pincher customers on “read”.

Price wars

Not a learning, we all know this. But without a 30% or more cost advantage vs competitors, dropping prices to gain market share has a 90% failure rate over the long-term. Price wars suck, and some industries are more susceptile to them than others. Figure out if there are price wars happening (or have happened) in the industry. Avoid starting (or participating in) them.

Perception precedes reality

Learning eight. (8) Sometimes pricing shouldn’t be about the financial cost in the underlying services or goods, but instead how the consumer perceives the price vs value/risk they take on.

Two things here that I found interesting:

Razor/razor blades model: I had heard of this before in relation to switching costs but not price. To recap: manufacturers often price the ‘rails’ of their infrastructure lower than the ongoing recurring prices so that consumers get a chance to try the product for a low upfront cost and get locked in on higher margin, recurring revenue. I.e. a razor is oriced cheap, blades cost more $$. The razor itself costs way more than the blades to make so the pricing architecture here is inverse to what logic or costs might dictate your end-price should be. Consider whether this pricing model is open to you to boost uptake as a challenger business.

Play their games: watch competitors - if they introduce a new pricing structure that seems to show (at first glance) that greater value can be obtained through their service but you know it not to be true, you can copy their pricing structure to allow consumers to compare apples to apples. If you’re right customers will see past the smoke and mirrors used by your competitor.

Extending an olive branch

Not really on pricing power, but I liked the info so I’ve included it. Pricing can be used to share business risk with customers. There are two main models and the authors’ views are as follows:

Pay per use - shares business risk with consumer, prices increase as the buyer increases its use of the offering. Means the start cost is lower, increases initial draw factor. Requires customers to be in growth mode (such that their volume or use of your offering can reasonably be expected to be higher in the future). Works best with switching costs and/or network effects. Commonly seen in software businesses. Makes less sense if your customers are mainly mature, no-growth firms.

Pay-by-performance - also shares business risk with consumer, prices are payable as the consumer derives value from the product/service. Eg. a solar installer is paid as the panel generates electricity by taking a cut of rebates or $ saved by the consumer. More complex, requires rigorous assessment of KPIs to determine price etc. While it might seem attractive, it carries risk around arguments of how pricing is to be calculated, etc. Problems can also develop if the consumer doesn’t use the product/service properly. Less customer control the better, but exercise caution with this pricing model.

Not all discounts are created equal

Learning nine. (9) there is no one-size-that-fits-all discount structure. Management should be thinking constantly about their discounts (if any) and how they are being deployed to drive the right kind of sales. Only this way will they properly harness their pricing power.

Volume based discounts don’t make sense if your end-users are established mature businesses who are unlikely to continue on their growth path upwards, but conversely if your customers are growing fast, the ‘bands’ for volume sizes can be wide apart (i.e if your order volume with us is between X and Y, you get Z% off) and actually used effectively.

Cross selling discounts don’t make sense unless your end users are currently consuming a lower margin good or service and you’re offering a higher margin one which they aren’t buying. In fact, offering discounts for customers who cross your product lines into lower margin products can actually be a net negative even though more sales = good (in conventional thinking). Consumer benefits should always be sweetest with the highest margin product.

If you a supplier, use off-invoice discounts to promote higher retailer prices (and therefore higher margins), or alternatively on-invoice discounts to promote lower retailer prices (and therefore increase volume on their end). This is because RRP is often determined by retailers based on their cost basis on the invoice. If discounts lower their cost basis they are more likely to lower the price of the good to sell more (and vice versa). Just another tool in the toolkit.

Changing price culture is hard

Learning ten, and this one is for all you high profile activist investors out there who definitely read my substack... >_> (10) Its not easy to change price culture. I’ve broken down how the authors think you could approach it into four steps. After reading these you might, like me, be acutely reminded of how simple humans are:

Foster & understand conviction in the need to maximise pricing advantages. More than mere lip service from the CEO. You need a compelling story and clear merit, as shown against business fundamentals. Use the 17.5% growth requirement example. Don’t even tell them its from 2003, our little secret. TLDR: the staff think “I understand why this is important”

Reinforce the change with a pricing strategy (including on discounts) and targeted intention behind that strategy to drive consumer behaviour in a certain way and maximise pricing power. TLDR: the staff think “I understand how we’re going to achieve this important thing”

Reward those at all levels who follow the new pricing strategy, including rewarding salespersons not for volume, but for high margin sales and less discounts. TLDR: the staff think “To be rewarded, I must follow this strategy”

Create new role models and ensure the CEO aligns with them - deify them for following the change and showing others. TLDR: the staff think “I am following the strategy for reward, but to go further and become deified, I must show others how to do it too.”

Wrapping up with some checklist additions

Here are some questions I’ve formed out of the book that I’m adding to my internal checklist (but also potential q’s for management if their releases don’t deal with pricing). Feel free to take some or all.

Who is ultimately responsible for pricing and what (rough) % of their role is occupied by pricing considerations? How are price changes administered through the organisation? How often does the responsible person re-evaluate pricing effectiveness?

Do you research customer attitudes (in relation to your own products, or your competitors) in detail, or mainly take the word of the sales team? Have you ever increased prices based on how well your service is perceived? Why do you generally raise prices (if ever) and how well has it been received by the market?

Roughly, what is the pricing strategy in place? Do you have any discounts built in and how easily are they given away?

Do you collect and analyse pricing data routinely (both for won and lost deals)?

Are you charging a premium or discount to your competitors? Do you think it is justified? Why don’t you charge more?

How focussed is the business on the gross margin?

Are all discounts, rebates, and incentives tracked for won and lost deals? Do you analyse this data?

What is the price variance on your products - do prices vary widely or are they stable? Do you only target ‘the best’ clients with discounts/incentives, or do you use them with pretty much everyone?

Are any discounts/incentives rule-based and strictly enforced by your team, or more ‘ad-hoc’ - or, ‘it depends’?

Do your sales/marketing forces have incentives to increase mainly (a) transaction prices; (b) transaction volume (c) both (please elaborate); or (d) neither.

Do you have fact based projections of overall pricing trends in your industries well understood by all in your organisation & if so, have they been accurate in the past?

How do you measure unexpected market shifts, particularly in relation to structural changes in your markets? Are you quick to adjust pricing?

Have you ever led a round of price increases among your competitors? How did it go down? Does someone else lead price increases in your markets?

Red flags; The CEO merely pays lip service to pricing power or overemphasises pricing strategy and ignores pricing incentives. They openly reward staff whose pricing performance is poor (even if their volume is good), or the firm gives discounts away easily or without a focus on higher margin customers.

Subscribe

And thats it! Just saved you from reading a few hundred pages of McKinsey textbook. You’re welcome. You can repay me by subscribing below. This also costs you… nothing…

I usually do stock-writeups on this substack. I’ve got a shortlist for the next candidate, but feel free to send any suggestions. This little extract was a one-off. If you enjoyed, let me know! I take summary notes for almost all books I read, and am happy to share more if you’re keen.